As some of you know, my current project is a book-length study of Africana religions and comics, where I consider how graphic formats are utilized for representing the spiritual traditions of black people. I keep getting sidetracked, though, because the sources are so diverse, and there are a million different stories that need to be told. So from time to time I want to post some of the more interesting themes that have emerged out of my research. Today’s topic has to do with my favorite subject, imagining Voodoo in popular discourses, which may or may not have anything to do with actual Africana religions. Recently, I submitted a piece to the serious and sagacious cohort of scholars at the African American Intellectual History Society blog in which I argue that the rise and fall of Voodoo in comics has been contingent upon myriad social and cultural forces that have historically shaped how we see black religious ideas and beliefs. Much like Hollywood Voodoo, Graphic Voodoo possesses a life of its own, with its own world views, plots, and personalities; but as I have suggested elsewhere, the prominence of the black superhero sets this genre apart by its fascinating use of religion as as a source of identity, empowerment, and self-creation, even with the mythical transformations that are typical of divine god figures.

As some of you know, my current project is a book-length study of Africana religions and comics, where I consider how graphic formats are utilized for representing the spiritual traditions of black people. I keep getting sidetracked, though, because the sources are so diverse, and there are a million different stories that need to be told. So from time to time I want to post some of the more interesting themes that have emerged out of my research. Today’s topic has to do with my favorite subject, imagining Voodoo in popular discourses, which may or may not have anything to do with actual Africana religions. Recently, I submitted a piece to the serious and sagacious cohort of scholars at the African American Intellectual History Society blog in which I argue that the rise and fall of Voodoo in comics has been contingent upon myriad social and cultural forces that have historically shaped how we see black religious ideas and beliefs. Much like Hollywood Voodoo, Graphic Voodoo possesses a life of its own, with its own world views, plots, and personalities; but as I have suggested elsewhere, the prominence of the black superhero sets this genre apart by its fascinating use of religion as as a source of identity, empowerment, and self-creation, even with the mythical transformations that are typical of divine god figures.  So what is it about these comics characters and Voodoo?

So what is it about these comics characters and Voodoo?

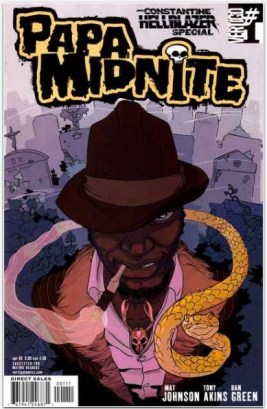

First, they are mostly male. Of course, black women do appear in leading roles in Graphic Voodoo narratives. For example, there’s the sexy exotic dancer alien who is inconceivably named “Voodoo” from the 1992 DC WildC.A.T.s comic. Back in the day, there was a Sister Voodoo. There are also numerous female Voodoo-inspired antagonists that seem to be drawn from true religious sources, such as the supernatural Marinette Bwa Chech, or the indomitable Marie LaVeau. Still, the presence of these female characters is subsumed by the more prominent male figures that we tend to think of, such as the famous Brother Voodoo, who would become the ultimate personification of African diaspora religiosity in the comics. Brother Voodoo, who was later transformed into Doctor Voodoo Sorcerer Supreme, enjoyed a brief but extraordinary run in the Marvel comics universe in the 1970s. Other characters such as D.C.’s Papa Midnite (1988), originating out of storylines from Constantine and the Hellblazer series, and Jim Crow (1995) from Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, united black masculinity and moral ambiguity into powerful personalities drawn from the liminal realm of New Orleans’ figurations of Voodoo supernaturalism. Rounding out the cast of these Voodoo brothers are villains and anti-heroes like Baron Samedi – not the Haitian loa but an actual nemesis of Captain America, an operative in a corollary organization to the secret criminal group HYDRA. We do not include the assortment of supernatural monsters, entities and Africanized deities that have come to be associated with Voodoo in the comics, beings that are generally constructed along an axis of good and evil, which doesn’t really work for us, since Africana religions tend to conceptualize ethics in pragmatic terms governing individual character rather than as fixed and rigid systems of moral concerns. So, what to do with a discourse that seems intent on replicating categories of stark dualism that also insist upon their effacement? The issue of the left and right hand, right and wrong, is something that plays out in again and again with narrative and visual forms in Africana religious thought. In most cases, graphic Voodoo and its characters are conceived within the category of instrumental magic – not religion – and deployed as a kind of powerful radioactive substance. In the comics realm, Voodoo heroes, whether houngan priests or sorcerers, are dangerous, unstable, and potentially violent.

Rounding out the cast of these Voodoo brothers are villains and anti-heroes like Baron Samedi – not the Haitian loa but an actual nemesis of Captain America, an operative in a corollary organization to the secret criminal group HYDRA. We do not include the assortment of supernatural monsters, entities and Africanized deities that have come to be associated with Voodoo in the comics, beings that are generally constructed along an axis of good and evil, which doesn’t really work for us, since Africana religions tend to conceptualize ethics in pragmatic terms governing individual character rather than as fixed and rigid systems of moral concerns. So, what to do with a discourse that seems intent on replicating categories of stark dualism that also insist upon their effacement? The issue of the left and right hand, right and wrong, is something that plays out in again and again with narrative and visual forms in Africana religious thought. In most cases, graphic Voodoo and its characters are conceived within the category of instrumental magic – not religion – and deployed as a kind of powerful radioactive substance. In the comics realm, Voodoo heroes, whether houngan priests or sorcerers, are dangerous, unstable, and potentially violent.

Still curious, digging deeper into the archives, I continued to search for the earliest Voodoo comics characters that I could find.  I was briefly diverted by a confusing jungle hero called Voodah, a brother who starts out as a muscular dark skinned Tarzan figure but who gradually and inexplicably turns colorless, then pink, by the fourth issue of the 1945 Crown Comics series in which he briefly appeared. Then, I came up short again with a somewhat lame white Doctor Voodoo by the name of Hal Carey who popped up in Whiz Comics for several episodes in 1953 as a square jawed missionary physician. But then, I surely struck gold when I located that which I believe to be the first recurring black character in the Graphic Voodoo genre – and where else would he be found, but deep within the

I was briefly diverted by a confusing jungle hero called Voodah, a brother who starts out as a muscular dark skinned Tarzan figure but who gradually and inexplicably turns colorless, then pink, by the fourth issue of the 1945 Crown Comics series in which he briefly appeared. Then, I came up short again with a somewhat lame white Doctor Voodoo by the name of Hal Carey who popped up in Whiz Comics for several episodes in 1953 as a square jawed missionary physician. But then, I surely struck gold when I located that which I believe to be the first recurring black character in the Graphic Voodoo genre – and where else would he be found, but deep within the African Haitian indeterminate jungle, storming through the bush with magic and fury, none other than Boanga, The Voodoo Man! crazed, loincloth clad, howling “Gamba Shema Lana” and deploying his Voodooism for murder, revenge, and general mayhem. It’s hilarious stuff, except that The Voodoo Man was pretty hardcore for 1937 when he appeared, pre-code, in a title role – a black criminal foil to the bland white leading men, and in the company of other comics luminaries such as Dr. Mortal, Sorceress Zoom, and Bird Man. What’s remarkable here is that even though The Voodoo Man is typecast as a black miscreant, his character is exciting enough to merit at least seven more appearances, and in each he terrorizes friends and foes alike with his astonishing tricks of sorcery, whic h include scheming for international crime rings, jumping through fire, necromancy, more howling, and hypnotizing white women to do stuff for him (but not the stuff that one might expect from a tall bare chested African savage with a fancy plumed headdress). Amazingly, clever Voodoo Man always escapes to live another day, probably due less to his indestructible nature than to his thrill appeal for the readers of Weird comics. I will return to this early black super-criminal at a later date; but I note that he does remind us that from the start, comics Voodoo in America has always been about race and power, with the problem of religion remaining the third rail of representation, as it is in most graphic productions involving black folk. This is why we want to know and understand this history. Africana

h include scheming for international crime rings, jumping through fire, necromancy, more howling, and hypnotizing white women to do stuff for him (but not the stuff that one might expect from a tall bare chested African savage with a fancy plumed headdress). Amazingly, clever Voodoo Man always escapes to live another day, probably due less to his indestructible nature than to his thrill appeal for the readers of Weird comics. I will return to this early black super-criminal at a later date; but I note that he does remind us that from the start, comics Voodoo in America has always been about race and power, with the problem of religion remaining the third rail of representation, as it is in most graphic productions involving black folk. This is why we want to know and understand this history. Africana

religions in the comics have historically found their expression in parody, stereotype, and caricature, with spectacular presentations that are perceived as visually arresting, violently racist, or ridiculously comical. As a discursive formation, Voodoo has come to represent an essential Africana spirituality and the locus of individual empowerment, while also imbuing notions of cultural identity with themes of (super)heroism and black agency. There is so much more that I want to say about Africana religions in the comics; but in the meantime, let us celebrate a true original, the notorious Boanga, one of the comics’ first but forgotten Voodoo Brothers. Gamba Shema Lana!

I am exceedingly grateful for the important work of the brilliant Afrofuturist William Jones, whose book, The Ex-Con, Voodoo Priest, Goddess, and the African King (2016), has inspired me to think in more complex ways about the nature of black comic heroism.