Call me hopelessly naive, but wouldn’t you jump to see a blockbuster film starring Bela Legosi and John Carradine called VOODOO MAN? I mean, how bad could it be? Maybe we might learn something about Africana religions. Or maybe we can see what this Voodoo thing is that’s so fascinating. What could go wrong?

Well, plenty, and if you watched the movie trailer, you are probably thinking, what the hell was that? That clip seems as unfathomable as this one here for VOODOO ISLAND:

Warning: I cannot explain what this movie is about

Now let’s try to deconstruct this trailer. It’s pretty awful, even though the movie is released about twenty years after the first Voodoo film, and the production values are superior. Sure, you want to laugh, but maybe you don’t know whether you should be laughing or not. But it’s no joke – this is not a comedy. So what are they trying to say? The ominous jungle music, white women being violated, tough men with guns, dolls full of pins, king crab legs falling from the trees, and danger! slimy human-eating cobra plants, and Boris Karloff. This must have something to do with Voodoo, right?

When I looked into the history of Voodoo-themed films in the United States I was surprised to find that scholarship had generally overlooked these contributions to American cinema. It could be that Voodoo is not perceived as a viable religion, and some find it ridiculous to associate such nonsense with sacred things. Despite the fact that black films and filmmakers willingly dabbled in the genre, and at least one early Voodoo film was written by an African American, Religion scholars focus on Christianity and the churches when analyzing film.  On the other hand, many prefer the antipathetic stand-in for embodied African spirituality, the zombie (from the Kikongo nzambi, which translates as “god” or “spirit-being.”) In fact, Zombie Studies is offered as a legitimate field of research by some academics, to the disgust of conservatives and evangelicals everywhere. So it is noteworthy that the earliest Hollywood movie to embrace the mythologies of Voodoo was Victor Halperin’s White Zombie, released by United Artists in 1932. And why was White Zombie such a big deal? For one thing, it was the first film to explicitly reference African-derived religions in the West, albeit in a stupid and contrived manner. But most significantly, the film introduced theater audiences to “Voodoo” as a very real, proximate, religious entity, thereby tapping into the visceral anxieties of American citizens at the time. And what could be better for the culture industry than a meme that provided stimulus to the emerging horror-story form, complete with a repertoire of elements from an imaginary religion upon which American fears and fantasies could be projected? Am I ruining the fun? Let me explain.

On the other hand, many prefer the antipathetic stand-in for embodied African spirituality, the zombie (from the Kikongo nzambi, which translates as “god” or “spirit-being.”) In fact, Zombie Studies is offered as a legitimate field of research by some academics, to the disgust of conservatives and evangelicals everywhere. So it is noteworthy that the earliest Hollywood movie to embrace the mythologies of Voodoo was Victor Halperin’s White Zombie, released by United Artists in 1932. And why was White Zombie such a big deal? For one thing, it was the first film to explicitly reference African-derived religions in the West, albeit in a stupid and contrived manner. But most significantly, the film introduced theater audiences to “Voodoo” as a very real, proximate, religious entity, thereby tapping into the visceral anxieties of American citizens at the time. And what could be better for the culture industry than a meme that provided stimulus to the emerging horror-story form, complete with a repertoire of elements from an imaginary religion upon which American fears and fantasies could be projected? Am I ruining the fun? Let me explain.

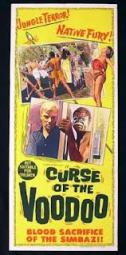

To understand the significance of the early film representations of Voodoo we must shift our gaze to the broader historical context in which these ideas developed. Between the years 1932 and 1962, some twenty-four Hollywood movies were released with the word “Voodoo” or “Zombie” in their titles. Assuming that these projects would result in box office gold, film creators merged “Voodoo” with arbitrary subjects, resulting in oddly juxtaposed titles like Voodoo Village, Voodoo Drums, Voodoo Tiger, Voodoo Puppies, and others (Okay I made that last one up).

The point is that “Voodoo” as a trope entered the cinematic lexicon at a particular moment in history – perhaps 1930 or 1931 – and thereafter took off as a self-perpetuating idea. Why? Well, the Motion Picture Code was put in place during these years, and horror film makers faced new restrictive guidelines for their unwholesome entertainment products. 1931 was also an inauspicious time in domestic and foreign matters, for the United States was facing a prolonged economic crisis, Hoovervilles had become fixtures in many major cities, and the military was embroiled in its 19th foreign intervention since the turn of the century – in Haiti of all places. And here is where we can pinpoint the origins of Voodoo as a discursive category. As all good students of history know, every military adventure, whether a nasty and brutish invasion for regime change, or an out-and-out shock-and-awe event for rapid dominance, requires the veneer of public support. In this case the military apparatus evoked the specter of menace with a brilliant strategy: they identified the threat of a malevolent, supernatural, black-faced enemy. And just to be sure that Americans were properly informed about the dangerous situation on the ground in one of the Caribbean’s most troubled political economies, a New York Times correspondent by the name of William Buehler Seabrook was dispatched to report on the “culture of the natives,” which he published in a book called The Magic Island (1929). Much has been written about Seabrook’s literary folly that I won’t repeat here. Suffice to say that this ugly little tome, many believe, was singlehandedly responsible for the hardening of negative social attitudes towards African diaspora religions, crudely lumped together under the rubric of “Voodoo.” Seabrook’s graphic descriptions of Vodou ceremonialism bore little resemblance to the actual ancestral religious practices of Afro-Haitians. But since The Magic Island was considered such an important eyewitness account, it is not surprising that the very first Hollywood venture to dramatize “Voodoo” would draw upon its ethnographic commentary as a primary source, and assimilate the text directly into the narrative structure of the horror format, with all of its fantastic and nightmarish imaginaries.

The point is that “Voodoo” as a trope entered the cinematic lexicon at a particular moment in history – perhaps 1930 or 1931 – and thereafter took off as a self-perpetuating idea. Why? Well, the Motion Picture Code was put in place during these years, and horror film makers faced new restrictive guidelines for their unwholesome entertainment products. 1931 was also an inauspicious time in domestic and foreign matters, for the United States was facing a prolonged economic crisis, Hoovervilles had become fixtures in many major cities, and the military was embroiled in its 19th foreign intervention since the turn of the century – in Haiti of all places. And here is where we can pinpoint the origins of Voodoo as a discursive category. As all good students of history know, every military adventure, whether a nasty and brutish invasion for regime change, or an out-and-out shock-and-awe event for rapid dominance, requires the veneer of public support. In this case the military apparatus evoked the specter of menace with a brilliant strategy: they identified the threat of a malevolent, supernatural, black-faced enemy. And just to be sure that Americans were properly informed about the dangerous situation on the ground in one of the Caribbean’s most troubled political economies, a New York Times correspondent by the name of William Buehler Seabrook was dispatched to report on the “culture of the natives,” which he published in a book called The Magic Island (1929). Much has been written about Seabrook’s literary folly that I won’t repeat here. Suffice to say that this ugly little tome, many believe, was singlehandedly responsible for the hardening of negative social attitudes towards African diaspora religions, crudely lumped together under the rubric of “Voodoo.” Seabrook’s graphic descriptions of Vodou ceremonialism bore little resemblance to the actual ancestral religious practices of Afro-Haitians. But since The Magic Island was considered such an important eyewitness account, it is not surprising that the very first Hollywood venture to dramatize “Voodoo” would draw upon its ethnographic commentary as a primary source, and assimilate the text directly into the narrative structure of the horror format, with all of its fantastic and nightmarish imaginaries.

The transformation of Haitian Vodou into Hollywood Voodoo was a process that involved the complicity of culture producers, the media, the occupying regime, the American government, the military, the church, and foreign corporate stakeholders. It was the inevitable outcome of relentless hostility and demonization of African spirituality that had begun centuries earlier, at the onset of a successful slave revolution in Haiti and subsequent national independence. No one, however, could have predicted the enormous commercial potential of the sensational fictions of Voodoo. How else, except at the movies, could one vicariously consume – without risk – in such an exciting mixture of magic, violence, animated brown bodies, and the hazards of physical survival in jungle environments? And where else could such a complete persecution of an indigenous African spirituality be so artfully re-imagined and repackaged as a new brand, exported as a commodity, and offered to the world as a virtual religion? My guess is that no one had actually seen anything like this in Haiti at the time, a struggling, traumatized nation in resistance to Marine occupation and the vise grip of foreign control, unless you stumbled into a Vodou ceremony stone drunk, bereft and paranoid, which is precisely how William Seabrook, lost generation journalist, drug addict, proud cannibal, and (eventual) psychotic, found himself, an authority on African religions in the western hemisphere.

The transformation of Haitian Vodou into Hollywood Voodoo was a process that involved the complicity of culture producers, the media, the occupying regime, the American government, the military, the church, and foreign corporate stakeholders. It was the inevitable outcome of relentless hostility and demonization of African spirituality that had begun centuries earlier, at the onset of a successful slave revolution in Haiti and subsequent national independence. No one, however, could have predicted the enormous commercial potential of the sensational fictions of Voodoo. How else, except at the movies, could one vicariously consume – without risk – in such an exciting mixture of magic, violence, animated brown bodies, and the hazards of physical survival in jungle environments? And where else could such a complete persecution of an indigenous African spirituality be so artfully re-imagined and repackaged as a new brand, exported as a commodity, and offered to the world as a virtual religion? My guess is that no one had actually seen anything like this in Haiti at the time, a struggling, traumatized nation in resistance to Marine occupation and the vise grip of foreign control, unless you stumbled into a Vodou ceremony stone drunk, bereft and paranoid, which is precisely how William Seabrook, lost generation journalist, drug addict, proud cannibal, and (eventual) psychotic, found himself, an authority on African religions in the western hemisphere.

Although I struggle to find something intellectually defensible to say about these movies, I am glad for the insights they provide for the critical consumer of film into the uses of “Voodoo” as cultural propaganda. And while we haven’t discussed the later decades of the twentieth century, when Voodoo-themed films reached their nadir with gems like Black Voodoo Exorcist and Voodoo Heartbeat, leave it to James Bond to redeem the genre with film number eight of the Bond franchise, the racially subversive blaxploitation hybrid Live and Let Die (1973). In this movie, once and for all, the Voodoo trope is immortalized by casting the civilizing presence of the gentleman assassin Bond against the deadly powers of Voodoo and its villainous henchmen. And because we understand how this thing works, we recognize sorcery and superstition as the true oppressors of the island natives, and not poverty, economic exploitation, and organized crime (mediated with coolness by Yaphet Kotto, as a smooth af code-switching drug lord). However, unlike the invasion of Haiti in 1915, this Marine does not stay to occupy, but instead bombs the shit out of the island, presumably in revenge for the threatened rape of his white woman’s pristine land by a gyrating witch doctor who wields a long, dark, writhing

Although I struggle to find something intellectually defensible to say about these movies, I am glad for the insights they provide for the critical consumer of film into the uses of “Voodoo” as cultural propaganda. And while we haven’t discussed the later decades of the twentieth century, when Voodoo-themed films reached their nadir with gems like Black Voodoo Exorcist and Voodoo Heartbeat, leave it to James Bond to redeem the genre with film number eight of the Bond franchise, the racially subversive blaxploitation hybrid Live and Let Die (1973). In this movie, once and for all, the Voodoo trope is immortalized by casting the civilizing presence of the gentleman assassin Bond against the deadly powers of Voodoo and its villainous henchmen. And because we understand how this thing works, we recognize sorcery and superstition as the true oppressors of the island natives, and not poverty, economic exploitation, and organized crime (mediated with coolness by Yaphet Kotto, as a smooth af code-switching drug lord). However, unlike the invasion of Haiti in 1915, this Marine does not stay to occupy, but instead bombs the shit out of the island, presumably in revenge for the threatened rape of his white woman’s pristine land by a gyrating witch doctor who wields a long, dark, writhing penis serpent while in trance (in a fine signifying performance). In the end, Voodoo is vanquished, or is it? …hard to tell, as in the final frames we see the crazy black psychopomp aboard a speeding train, propped up on the engine’s helm and laughing wildly, probably on his way to another date with death.

…hard to tell, as in the final frames we see the crazy black psychopomp aboard a speeding train, propped up on the engine’s helm and laughing wildly, probably on his way to another date with death.

The cultural history of Africana religions in the New World (including Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santeria, and American Hoodoo) and their representation in popular culture and film can be a rich and illuminating field of study. However, in the realms of contemporary virtual media, performed “reality,” and digital simulation, it can be challenging to determine what is authentic and what is not. And while some of us may find most depictions of African-derived religions on film to be utterly offensive to our sensibilities owing to their racist, xenophobic, and misogynist bent, they are a valuable index for gauging the production of culture as well as the concomitant anxieties and interests that accompany cultural products in real-time. But there is a another issue at stake. Representations of religion on film have become the perennial means by which the imperial American regime articulates its missionary rationale in the world, by pitting the forces of civilization and morality against the barbaric, non-Christian Other. What makes “Voodoo” distinct is its formation in an historical moment when the military agents of the organized persecution of a religion elided their own presence and actions by identifying themselves as the putative victims of the Voodoo horror, its depraved insurgents, and their wartime atrocities. And although these specific associations between Africana religions like Vodou and the virtual religion of Hollywood Voodoo are less immediate now, similar themes will be revisited by generations far removed from its sources, long past the expiration dates of its provenance in Haiti during the occupation. Looking ahead towards the final decades of the twentieth century, we see the cycle complete itself, and begin again. Look, quick! For Hollywood has found itself another bizarre religion! Consider, if you will, the film treatment of contemporary Muslim subjects. While not yet approaching the extremes of cinematic horror, one can imagine the fertile possibilities, perhaps in the insidious coding of the phony gods ‘n false prophets theme or the religion-of-superstitious-fanatics genre, or perhaps re-spun more creatively into a “jinn-possessed blood lusting jihadi zombie” meme. That might be interesting. So look closely, and you might even find the sodden remnants of the Hollywood Voodoo trope draped over movie depictions of Islam like a filthy blanket – rank, despicable, but strangely familiar.

What makes “Voodoo” distinct is its formation in an historical moment when the military agents of the organized persecution of a religion elided their own presence and actions by identifying themselves as the putative victims of the Voodoo horror, its depraved insurgents, and their wartime atrocities. And although these specific associations between Africana religions like Vodou and the virtual religion of Hollywood Voodoo are less immediate now, similar themes will be revisited by generations far removed from its sources, long past the expiration dates of its provenance in Haiti during the occupation. Looking ahead towards the final decades of the twentieth century, we see the cycle complete itself, and begin again. Look, quick! For Hollywood has found itself another bizarre religion! Consider, if you will, the film treatment of contemporary Muslim subjects. While not yet approaching the extremes of cinematic horror, one can imagine the fertile possibilities, perhaps in the insidious coding of the phony gods ‘n false prophets theme or the religion-of-superstitious-fanatics genre, or perhaps re-spun more creatively into a “jinn-possessed blood lusting jihadi zombie” meme. That might be interesting. So look closely, and you might even find the sodden remnants of the Hollywood Voodoo trope draped over movie depictions of Islam like a filthy blanket – rank, despicable, but strangely familiar.

Thank you for this very insightful look at the emergence of pop-culture “Voodoo.” I have not seen a number of the films you mentioned, but of those I have your statements ring true. The power of the white gaze on the exotic Black “other” displays a number of the cultural fears which had been bubbling up during the early-to-mid twentieth century. I think it is very interesting that an African American screenwriter or film-maker bought into the hype as well, but it says a good deal about the difficulties Black film artists faced as they worked to establish themselves in Hollywood (or even outside of it).

I did want to note that I think the exoticism you’re noting here goes back even into the teens and twenties of the 1900s. For example, performances at the Cotton Club in New York (where Black performers did shows for white-only crowds) frequently featured “tribal” dances of half-naked (or fully naked) African Americans. The dancers would wave spears and shields, parade in tiger-print loincloths, and do any number of other signifying acts demonstrating “African primitivism.” Some of the old posters from that era show signs of those performances:

http://file.vintageadbrowser.com/l-cd73tk25h3ivke.jpg

http://www.anabenaroya.com/pop%20ups/lincolncenter.html

(There’s also a really fine example in Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s History of the African American People, but I can’t find that image online).

I imagine that this phenomenon has even deeper roots (I’m thinking here of the Kongo Square dances of Marie Laveau), but I think you really hit on something here in pointing out that the inter-war period became an intensely fruitful era of cultural exploitation.

Thank you for a fine blog and a fine post! Keep up the great work!

All the best,

-Cory (New World Witchery)

Thanks Cory, I really appreciate that. There really is a lot to look at in this area.

Very nice piece. I actually have the lobby card for Voodoo Village. But personally I can’t get over Bela Lugosi’s eyebrows and intend to write about them myself very soon.

thank you Lilith that means a lot. I actually think there is an entire study that might be done on Bela Lugosi’s eyebrows and the semiotics of satorial adornment, and I think you should write it LOL

That sounds fantastic, consider my scopophilic eyebrows raised :)

Thank you for writing such an interesting piece and I can’t believe I have only just come across this! Mainly because I happen to be researching How Hollywood misrepresents Vodou for my Anthropology dissertation. Even in films that have been made in the last 10 years still go by this stereotype that Hollywood has created. It can be seen throughout years of Hollywood films that they typically try to find at least one culture that they can exploit to make a movie out of (thought this could just be one of my rants but i will stick to it.). The amount films produced in the last 10 years just about going to war and almost romanticising it is shocking.

Anyway, this is brilliant blog and post and I certainly keep reading this.